In the mists of London, at the heart of a nineteenth century torn between Victorian restraint and creative fervour, a silhouette emerges…slender, delicate, almost unreal :

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, whom everyone would one day call “Lizzie,” moves through the city like a poorly kept secret.

Very quickly, she becomes the quiet obsession of the Pre-Raphaelites, that circle of revolutionary artists founded by Rossetti, Millais, and Hunt.

It is John Everett Millais who will turn her into an icon with his painting Ophelia, now exhibited at Tate Britain in London.

Ophelia—the young woman floating in a stream, on the edge of madness—is one of the most moving figures of Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamlet.

Ophelia dies very young, consumed by grief, a witness of control and manipulation, for she sinks into madness after her father, Polonius, is murdered by her lover, Hamlet.

A mind that chose another way of surviving once the world around her became unbearable. Her descent was not a failure…it was a rational and heartbreaking response to a world that offered her no other choice.

The Pre-Raphaelite painter created the landscape of the painting while staying with his friend William Holman Hunt on a farm in Surrey during the summer and autumn of 1851.

He needed these two seasons to depict the stream and the flowers, not all of which bloom at the same time. Some are mentioned by Shakespeare in the play, while others were added for their symbolic value.

For a long time, history reduced Lizzie Siddal to a mere muse…the beautiful Ophelia, the flame-haired lady.

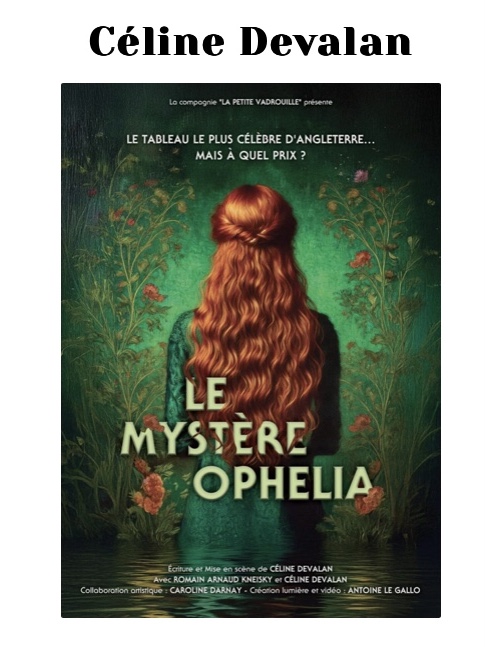

But our era revisits Victorian myths and culture and in 2025, it would be Céline Devalan, author and stage director trained at Cours Florent and the Théâtre National de Chaillot, who would pull Lizzie out of Millais’ canvas to bring her back to life in her play Le Mystère d’Ophelia.

It is up to us to understand how all of this might have happened, to reveal it to you.

For there are places that exist only in the fragile space between a painting and its viewer.

A suspended space, an echo chamber where the voices of the past mingle with those of the present.

It is there, at the edge of still water, that this story begins.

Lizzie is sitting on a mossy rock.

How to describe this woman born in 1829…milliner, model, painter, poet…whose pallor seems to absorb the light?

She has kept from her earthly passage a feverish gentleness, a timid smile, and, in her eyes, that shadow Victorian society never wished to see.

Around her, the grasses sway as if the canvas itself were breathing.

The water flows, clear and silent, ready to welcome once more an Ophelia who will not drown again.

But Lizzie is waiting for someone.

A woman appears around the bend in the path.

Red-haired, modern, sharp-eyed.

She holds a notebook pressed to her chest, like a paper heart.

It is Céline Devalan, writer, director, coming from a time when women may finally speak…but must still, sometimes, fight to be heard.

Lizzie rises, startled.

Lizzie — You… can see me?

Céline — How could I not? I’ve been searching for you for years.

Lizzie — No one ever searched for me. They simply looked. As one looks at an image.

Céline — That’s why I’m here. To give you back a voice. A story. Your story.

Lizzie smiles, as if a weight lifts from her. She begins to speak, softly.

Her modest childhood in London, her work in a hat shop.

Then her encounter with the Pre-Raphaelites: Deverell, Hunt , Millais, Rossetti.

The long posing sessions, the freezing baths, the tuberculosis lurking.

And her love for Dante Gabriel Rossetti: an artist’s passion, a passion of possession.

Céline Devalan listens, then speaks in turn.

She tells her own path: theatre as refuge, as weapon, as truth.

Her desire for an art that is both popular and poetic, her need to tell stories that disturb, illuminate, captivate.

She speaks of writing Le Mystère Ophelia, of the deep necessity to give a human face back to the forgotten muse, to restore the place Lizzie deserved in the history of art—and from which she had been erased.

Lizzie — You wrote about me.

Céline — No. I wrote for you.

Lizzie — How strange… I was so often depicted, never heard.

Céline — I wanted to listen.

The setting trembles, as if Millais’ canvas unfurls around them.

Flowers float without falling, lights glide like brushstrokes. The Ophelia of the painting murmurs from afar. Lizzie steps closer.

Lizzie — Why me? Among so many forgotten women …

Céline — Because your silence was shouting. Because they confused you with a fictional dead girl, and that confusion swallowed you. Because they remembered the muse but erased the artist.

Lizzie — I was Ophelia to them.

Céline — And you are Lizzie to me.

Words shatter like glass under light.

The dialogue continues by the water.

Lizzie — Are you ever afraid that stories might devour you?

Céline — Often. But I write them so I don’t lose myself.

Lizzie — I didn’t know how.

Céline — It wasn’t your fault. You lived in a world that denied women the slightest escape.

A breath of air passes. Lizzie inhales deeply, as if breathing in the century she was denied.

Lizzie — And what do you want me to become in your play?

Céline — Not a victim. Not a muse. A woman who tried to exist, freeing herself from her condition, imposing her vision as an artist…as a woman!

Lizzie — Then write me that way.

Céline — I already have.

Céline opens her notebook. The pages rustle. The lines she wrote turn into fireflies around Lizzie.

A new light glows on her face.

Lizzie — Is this what it means to be alive?

Céline — Perhaps…surviving ! To be told differently. To be seen differently.

Lizzie reaches toward the water.

In its surface she no longer sees a dying Ophelia, but a woman standing tall.

The two women face one another, suspended in time.

Lizzie — Thank you for finding me.

Céline — Thank you for captivating me that day at the Tate Gallery.

Lizzie — Take me with you.

Céline — I do. Every night at Theatre. On stage.

The lights fade slowly. Only the echo of a recovered voice remains.

Céline smiled, closed the notebook, and returned to the real world, where Lizzie now waited for her each evening…on stage. In the light, alive… forever.

The wind of Avignon brushed her face as she left the theatre.

The evening sky, still warm with sun, seemed to quiver slightly… as if an invisible thread were still tying the playwright to the other world, the one where water floated in the air and where a red-haired woman spoke at last with her own voice.

Céline breathed in deeply.

The murmurs of the departing audience, their laughter, their comments…all of it sounded like a reassuring, earthly echo.

She thought: The dream has crossed into the stage. That is where it will remain.

An independent journalist awaited her in a quiet café near the ramparts. She wished to discuss what made Le Mystère Ophelia so singular.

Céline arrived with a notebook under her arm, a hint of fatigue in her features, but a new clarity in her eyes.

They sat.

The recorder clicked.

The conversation began:

—Your play seems inhabited by a presence, a breath. Where does this sense come from…that the border between reality and imagination is so porous?

“I truly believe that some stories do not settle for being told—they return. Lizzie Siddal is one of them. When I began working on Le Mystère Ophelia, I felt something strange… and gentle… as if she was speaking to me, walking by my side like my shadow. Not a voice dictating what to write—rather a breath, a discreet presence at the edge of the page. It felt as if Lizzie walked between two worlds, and I tried to follow her.”

—Is that why you open the play with a dream-like passage, where the Lizzie of the past speaks to us with almost contemporary intensity?

“Exactly. I wanted to break the idea that Lizzie belongs to the nineteenth century. To me, she belongs to the in-between! And in that floating space, she can finally reveal herself, tell what was never written, speak with us, become alive again.But she isn’t a ghost. She isn’t a revenant. She is a woman who was forgotten while still alive, and who now demands to exist.”

—When you closed your notebook last night, did you feel Lizzie was leaving you? Or staying?

“Lizzie never truly leaves me. She is within me, and reappears… She moves between pages, scenes, dreams. Between the world where she lived and the one where we now perform her story. I believe she continues to walk between those two worlds, and that theatre finally gives her a stable, luminous, breathable path…Every night, when I step on stage and the audience holds its breath, I tell myself: Here she is again… and this time, she speaks.”

—After the success of Le Mystère Ophelia, you are preparing a new project for 2026: Return to the Limelight. What is this piece, and why choose such a unique venue as the chapel of Highgate Cemetery in London?

“Return to the Limelight was born from my desire to question memory, disappearance, fame, and oblivion. I’ve always been fascinated by the flamboyant—and often tragic—lives of artists who lived under the spotlight, then sank into shadow… into night… into forgetting.I wanted to build a bridge between those extinguished lives and our present. This piece is not a tribute, but a repair. Repairing what history deliberately left aside, restoring it to the place it deserves.”

—What is the dramatic material of Return to the Limelight?

“The piece aims to express a universal truth: the fragility of fame, the weight of the gaze, the passage of time. We speak of love, art, regrets, wild tomorrows and shattered horizons. But above all…the desire for reappearance: to make what was asleep live again.”

—You have already worked with La Petite Vadrouille, and you clearly enjoy staging that mixes text, imagery, poetry, and space. How will this aesthetic manifest in the new project ?

“The aesthetic will, I hope, be worthy of the subject. Highgate Chapel is not a traditional theatre—no wings, no proscenium.The stones and stained glass, the candle shadows, the echo of footsteps—all of it becomes part of the staging.We plan to use voice-overs, candlelight, a Victorian atmosphere, texts that sound like inner monologues or direct addresses to Lizzie’s loved ones.The audience will be within the work: between the visible and the ambiguous, the tangible and the spectral.I want each person, when the lights fade, to feel the weight of a life once lived—but also the possibility of a rebirth.”

—What challenges do you anticipate? And what do you hope to offer the London audience (and beyond) ?

“Several challenges. First, the venue itself: a historic, protected chapel, with technical constraints : acoustics, the choice of light , safety. Everything must respect the place, its history, and yet create a living, sensitive, welcoming space.Then the audience: inviting them to accept a blend of the poetic and dramatic, asking them to step into a space of memory, fragility, gravity… a passage.And of course, the language barrier because I speak English… with my slight … French accent! So I plan to play on that too…because Lizzie is an English lady …but she came to chat with me ! I hope everyone leaves with the idea that memory can save what we believed lost.”

—Do you have a message for those who will come to see the play in London on 22 and 23 September 2026?

“Yes. At its core, Return to the Limelight is more than a performance: it is a promise… that the light, even fragile, can return to Lizzie Siddal.”

Event details:

https://highgatecemetery.org/events

The journalist put away her recorder.

The click of the device seemed to mark the end of a chapter.

Céline remained still for a moment, her fingers around a cup now cold.

A draft slipped through the café window, lifting a lock of hair and trembling the tablecloth.

The playwright looked toward the busy street: passers-by, laughter, the shimmering midday light on the cobblestones of Avignon.

Reality…indisputable, solid.

And yet…

When she rose to leave, her notebook slipped slightly from her bag.

It opened on its own, as if moved by an unseen will.

A single page, blank the day before, now bore a faint line, almost a shadow of graphite.

A reclining silhouette, peaceful.

A woman with flowing hair.

A face turned toward the inspiration , thé light: Lizzie Siddal !

Moved , Céline closed the notebook gently, a quiet smile on her lips. She did not know whether this apparition was a remnant of a dream, a spark of memory, or a hand extended from the other side.

She simply welcomed it with a new certainty: as long as words are written, as long as voices are carried, as long as stories find new life, Lizzie Siddal will never disappear. Céline Devalan crossed the street, holding the notebook against her heart, and walked toward the theatre where, that very evening, spectators were already waiting for the curtain to rise.

And somewhere, between two worlds, a red-haired silhouette walked beside her—unseen by others, profoundly real to her.

The story continued… like a breath.

Like a light that never goes out.

Because intelligence alone reasons, builds, and organizes. But intelligence that opens itself, that places itself in the service of the human…then yes, it touches the heart, becomes a bridge between two beings and recognizes the sensitivity, the memory, the fragile light of an emotion.”

Copyright Ely GALLEANI